A stone, a leaf, an unfound door, of a stone, a leaf and a door. And all of the forgotten faces.

-Thomas Wolfe, Look Homeward, Angel-

△Barbara Pollack/Art Critic

In another more playful installation, Record, 2000, Young printed 30,000 cards with pictures of stones and wood which he arranged on a gallery floor. On top of the cards, he placed stumps of tree branches and stones, dispersed throughout the space. To advertise the installation, he also printed stickers with the imprint of a stone, which he put out along the streets leading to the gallery. People followed the stickers and discovered the installation, but as soon as they entered the gallery, they disrupted the pattern of the cards on the floor. Sometimes, children came in to play with the cards, just as Young had played with sticks and stones as a child. Every morning, he had to get up and laboriously put the cards back in place.

Highly creative and experimental, Young's installations always push the gallery space to its very limits. Instead of the traditional “white cube”, empty except for rare objects and paintings on view, these installations overtake the space and reconfigure it into a more interactive environment. Whether it is the aroma of perfume or the fluttering of butterflies, the space infiltrates the viewer's senses and much more than sight is needed to appreciate the work. By doing this, Young is transformed from being a picture-maker into more of an architect, designing the experience through his use of space.

Moreover, while his innovations in installation art might be read as “western” or at least, “global,” his intent and use of materials is influenced by Korean culture, Confucianism and Zen. Young's frequent use of text is reminiscent of calligraphy, brought out to the fullest extent in some of his later paintings, in which he applies paint to canvas in the flinging brushwork of ink painting. Turning something as rudimentary as a stone into the focus of his art-making coincides with spirit and principles of Asian philosophies who rely on nature as inspiration for meditation. While the same can be said for many other Korean artists who derive inspiration from Korean culture. But often their works are somewhat provincial and limited. Young is able to infuse his installations with a global vocabulary, allowing them to be appreciated by audiences from both sides of the world.

Korean cultural influences are in the foreground of Young's paintings of the last decade--mural-length white canvases, marked by gestural punches, pencil scribbles and jarring textures. These paintings bear a strong relationship to classical scroll paintings, both in their dispersive composition and their long format. It is not surprising when Young tells me that they are all landscape paintings based on memories of his hometown. After readjusting my eyes, I can make out boulders and rock formations, pine trees and temples, all against a stark white background that could be snow. Some are applied to multiple panels, like folding screens. In all, the paint is applied with a vigorous gesture, splattering and defying control.

“This is the traditional and natural landscape of my hometown, but I want to express the beauty of space in a simple way. And even though it is made up of natural things, the spirit is a modern spirit. I want to deliver the message of nature but I want to look modern.”

Indeed, even though the work may look apolitical, the Korean landscape is charged for an artist like Young. While some of the works specifically relate to his hometown, others refer to the scenic mountains of North Korea, a subject that comes from Young's desire for his country to be reunited. Even those referring specifically to his youth betray his conflicts about his upbringing. He often felt repressed by the teachings of Confucianism, which required him to worship his ancestors. Looking towards his future, he had to leave but he misses this landscape all the same.

“I want to express the energy repressed within my body. I have always tried to escape from the social system. My trial and error is expressed in these paintings. I want to express more energy into my artwork.”

As opposed to a scroll painting where all the elements are composed in the very essence of serenity, Young's paintings are explosive and bursting with free expression. By 2005, he is literally attacking the canvas, aggressively punching it and pounding into its surface. Rather than approaching a painting as an empty space that needs to be filled, he is using the blank void as an element in his composition. His gestures are almost like performances, leaving only the results for the viewer to see. The explosion of energy used to make these works is palpable as clearly indicated by the powerful markings.

This combination of painting and performance is highly innovative, though it can be seen as rooted in American Abstract Expressionism. Like Pollock, Young applies paint as an extension of the body. But, this artist does not cover the canvas with overall layer of paint, as Pollock did. Instead, he leaves much of it blank, inviting viewers to venture into the void. In this way, Young's work closely relates to that of the Gutai movement, which took place in Japan in the 1950 sand 60s. The Gutai Manifesto urged artists to rebel against every tradition of art making and to defy the conventions of society. Gutai artists made work by bursting through screens and using their feet to apply paint to canvases. Like them, Young is putting his whole body into the work out of defiance of society, more than a mere artistic technique.

Despite the similarities of Young's technique to these two art movements--abstract expressionism and Gutai--his final results are clearly original. He does not even consider his work “abstract” as it is always closely related to his considerations of the landscape and nature. His challenge is to embue traditional landscape painting with a contemporary approach to composition. Ironically, by dispersing his markings to the edges of the painting, he comes up with work that may be his most “Korean.”

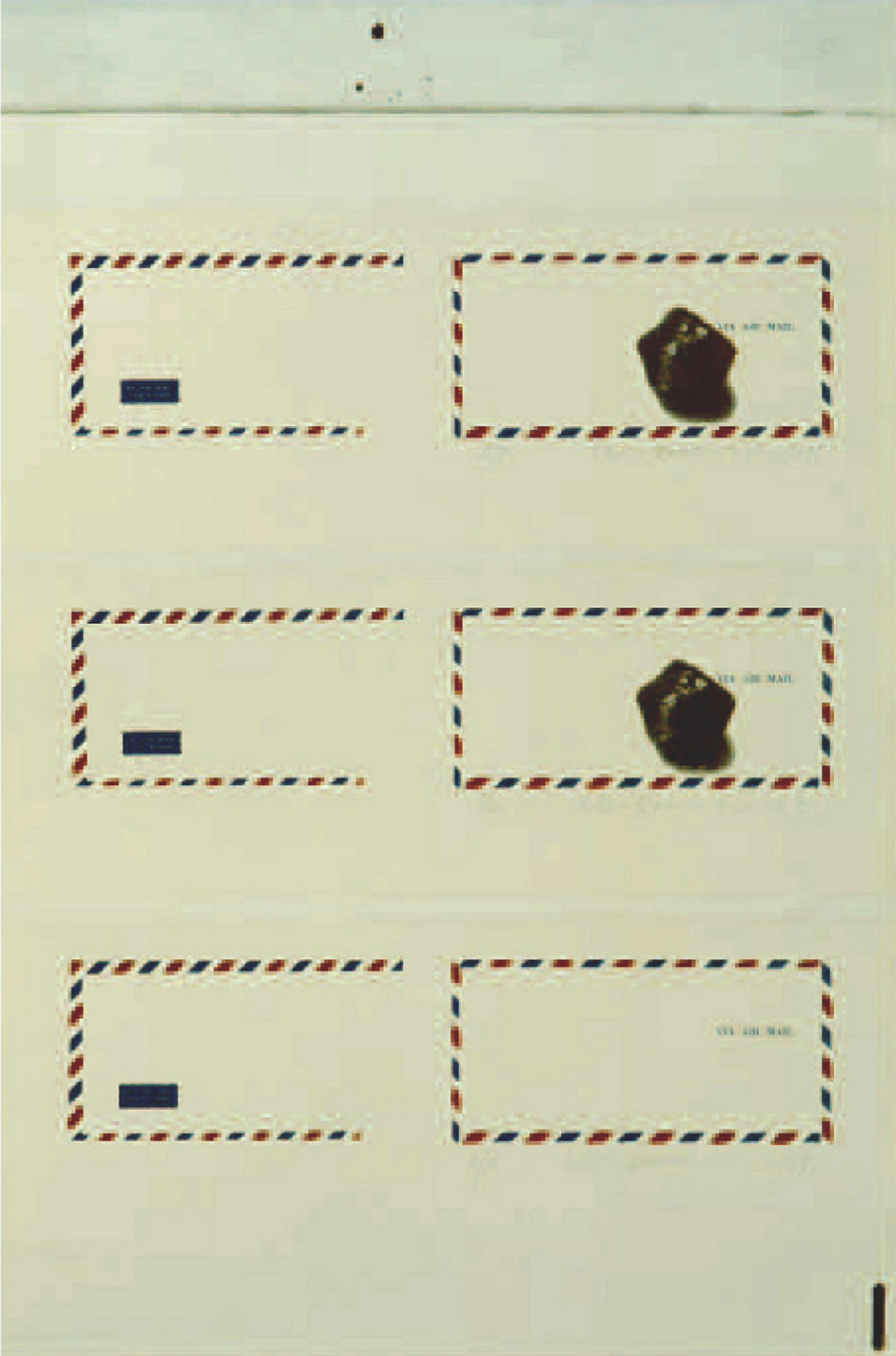

Given his respect for emptiness in these paintings, it is not surprising that his next move as an artist would be to literally create an empty space in the surface of the canvas. To create this result, Young employs yet another new technique of his own creation. This time, instead of applying stones to the painting, he inserts a wad of aluminum foil into a small box in the painting, fills the hole with plaster and removes the material when the plaster is dried. This leaves an irregular shaped opening in the center of the painting which looks as if a stone was pulled from its interior. At first the opening is almost invisible, a black hole in an entirely black painting. But then, after examining it for several seconds, the brushwork and various markings are seen and the hole comes into focus.

Few viewers examining these works will be able to tell that each hole is entirely individual. It is Young's secret. In fact, though the openings are similar from painting-to-painting, he is leaves different patterns and textures on the interior. The unique qualities of each, however, can only be found by examining inside the hole which is nearly impossible without a flashlight. Only then, can you see the ridges and indentations that make the work truly original. Young believes that he is inserting spirituality into each work by creating this space. But, by making a space that looks like it occurred naturally, he is returning to the theme of nature as enduring while human nature is subject to whims and changes.

“I am a very energetic person but living in the countryside, sometimes I am very frustrated. Confucianism dictates that you follow your ancestors rules, so I felt frustrated and limited by that. I am the eldest son in my family so everything was passed on to me. That's why I feel free ever since I escaped from my hometown. Even though I have the spirit of freedom, when I go back to my hometown, I cannot express all my feelings.”

Inverting the stone, so it no longer protrudes from the painting but burrows inside the work, makes this some of Young's most personal work. The absent stone--a fabricated illusion that is entirely convincing--symbolizes loss, a trace memory of something that no longer is there. For this artist, it is specifically the natural setting of his youth, represented by a stone. But it could also be the loss of nature in modern life, the situation for most people in the urban centers of the 21st century. At the same time, this absence is not necessarily a negative issue. After all, it is only after Young left his hometown that he could become an artist.

To Young, these latest artworks are his most free, defying all conventions about traditional painting. Each work is more akin to assemblage than painting, incorporating 3-dimensionality into the composition. The opening confounds our expectations of a painting, yet it is impossible to miss. We keep staring at it, wanting it to convey its secret. But for each viewer, it will have an individual meaning, a sense that something is missing from their lives. Young can point to nature, or his childhood home, as the element now gone. But it is clear, from his entire body of work, that his main concern is a loss of spirituality and of a unified identity, now mere remnants of the past in contemporary life.

According to Confucianism, when you reach the age of 50, you need to empty your mind. So now I need to make an empty spirit and pour my energy into the artwork. I don't know what will happen in the future but for the time being I want to focus on emptying my mind.

◇Barbara Pollack

Art Critic and Curator, International Art Critics Association, USA.