A stone, a leaf, an unfound door, of a stone, a leaf and a door. And all of the forgotten faces.

-Thomas Wolfe, Look Homeward, Angel-

△Barbara Pollack/Art Critic

The long journey from home to the strange place called art can be mysterious, treacherous and risky. But, for those who become artists, it is also a movement towards a more magical state of creativity. often a distant destiny from the place where they were born. In traveling this journey, an artist sometimes finds that many of the things he played with as a child (and then rejected in youth) become key elements in his artworks. This can be true for all artists, no matter what country or culture they are from. But, for many artists in Asia, who have lived through their countries' transformation over the latter half of the 20th century, nostalgia for childhood playthings is made all the more poignant by the fact that the place that once was home no longer exists, eradicated by modernization and homogenized by globalization.

Korean artist Jeong Jai Young is a very lucky man in that he can go home again to his place of birth, the countryside town of Yecheon in Gyeongsang Province, where ginseng is sold in vast markets and remnants of one-story framed houses remain. It is a three-hour drive from Busan, the seaside resort where he now lives, but he makes the trek willingly to revisit the Confucian temple, to see the pine trees and to gather stones for his art works. This is an artist who is definitely adept at contemporary art practices, but who is rooted in the natural landscape of his youth. He has traveled a far distance to arrive at his latest works, near abstract canvases with cavernous indentations where he inserted a stone, then removed it, leaving a distinct pocket of air. Stone is central to his art-making, though he is not yet a sculptor. In painting, drawing, print-making and installation, he has examined the shape and weight of stones, creating works that recall nature even as they are essentially man-made.

“I'd like to explain how I introduced stone into my artwork. I took many walks on country roads and noticed that everything is scattered with stones. Maybe it would be the same in the US, but when I was young in my hometown I played with stone and soil and earth. I was obsessed with that memory from my childhood. When I went back to my hometown as a grown man, I saw that everything was still covered with stones. I was frustrated and shocked by the scene which motivated me to make art work about the stone,” says Jeong Jai Young.

Balancing natural and artificial elements, Jeong Jai Young has come up with a unique vocabulary for expressing his ideas. His theme is often the durability of stone, a symbol for all nature in his work, in contrast to the ephemeral quality of human life. He has drawn from his Korean background using calligraphy as a technique and Confucianism as his outlook. But, Young is also entirely contemporary, fusing painting with performative actions and installation with interactivity. He works fluently in a variety of mediums in ways that distinguish him from less experimental Korean artists. At the heart of his projects is his unbridled energy, bursting in many directions at the same time. Yet, underlying this expressive exhibitionism is a subtle internal inquiry that nudges viewers into examining the absence of nature in their lives and the emptiness caused by this loss.

“From birth to death, people can normally live a maximum of 100 years. And it seems to me that in the course of life, the human mind changes a lot. I was attracted to stone by the fact that stone does not change.”

Young traces his development as an artist from 1987, the time he was a sophomore at HongikUniversity, just a year before Koreabecameademocraticstate. As opposed to an older generation focused on political issues and protesting the military dictatorship, Young was part of the New Generation who turned away from politics and concentrated on more personal concerns. After an early period of experimenting with abstraction, this artist soon began to invest his works with literal references to nature, specifically the symbol of a stone. Young then juxtaposed commercial packing and logos with his natural materials as a pointed critique of the rampant consumerism of Korean society in the 1990s.

“People normally purchase clothes, cars and Coca Cola as well. but I wanted to commercialize a stone of my own,” says Young. “As you know a diamond is also a stone but most stones are just kicked and abandoned.”

In one project, Young created wooden boxes to package stones, then sold them as luxury goods, one to a customer. He stamped postal envelopes with the image of a stone and sent out this altered mail to dozens of individuals. Yet another time, he filled a gallery with smelly crates from a fish market on one side and boxes scented with Paco Rabanne perfume on the other, a symbolic conflict between the natural and the synthetic. These installations were radical departures for the artist who was trained as a painter. By incorporating an element of performance into the work, Young anticipates the current trend in relational artworks, art that incorporates audience participation.

In these works as well as many others, Young is adopting stone as a kind of “ready-made,” like Marcel Duchamp's urinal or bicycle wheel. But in this case, the original found object is not industrial or man-made, it is natural and readily available. In this way, the artist is pushing the very dialogue about the original and reproduction, since in Young's case, each stone is an original and unique, whereas in Duchamp's artworks, the ready-made is a reproduction, manufactured multiple times. However, due to the sheer abundance of rocks in a landscape, it is evident that anyone can “own” a stone. It takes a very talented artist to turn such an easily obtainable element into a valuable work of art.

This examination of originality is most pronounced in the installation, Dolmen, 1992, in which Young painted a stone bright blue and outlined its form with thin blue line of neon. According to the artist, this work focuses on stone's dual use, as an element of nature and as the foundation of architecture. In this case, the blue line both accentuates the stone's unique shape and demonstrates how a one-of-kind-object can be replicated. There is a tension between the stone and the light, as opposing forces. But there is also a harmony, as if the light is a halo adorning the stone.

“I wanted to create a real situation, even if it is fake. I want to convey my real feelings to the people. That is why there are stones and texture.”

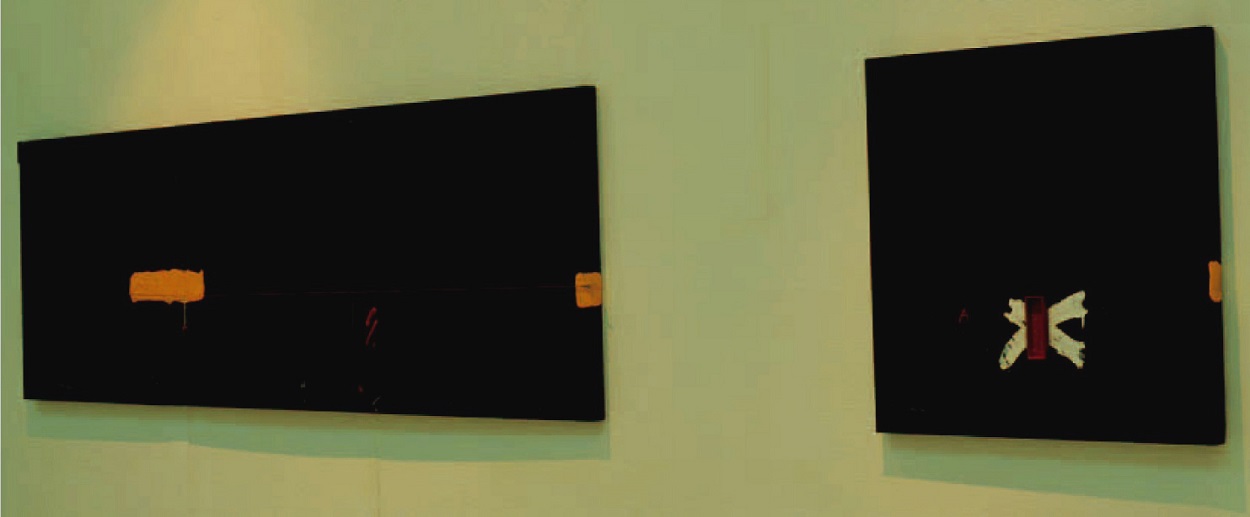

Percipitation (like-150mm), painted in 1991, is a turning point for Young who was just 27 at the time. The title, later applied to many works he has made since then, refers to a weather report that 150mm of rain would fall in Seoul. Shocked by the figure, he wanted to make a work that conveyed the power of nature to impact even technologically advanced lives. He painted a line of beakers, each holding a stone, in a science laboratory of a painting. Three years later, he painted Like-150mm, 1994, an even more experimental work. For the first time, he embedded actual rocks deep into the surface of the painting and scribbled ‘Like 150mm’ on the lower right hand corner. It is an aggressive work with the almost violent intrusion of stone. Yet it is also meditative, painted in a palette of black-on-black, that invites contemplation of its unique texture.

An even more aggressively “real” situation occurred when Young brought ten truckloads of rotten wood and filled a gallery to its ceiling to create the installation, History-like-150mm, 1999. The wood had been left outside for three years, exposed to storms, and as is natural, became the refuge for microorganisms, insect, worms, flies and butterflies. Soon, the gallery was overridden by bugs, flying through the air. Young considered the work a success because he had demonstrated that he could “revive” nature even in a sterile setting, celebrating its fundamental role in life as well as its power to infiltrate and take over man-made environments. But as an artwork, this installation is highly subversive. By using something as common place as stacks of rotten wood, he is again inserting a critique of consumerism, defying his audience to buy, or even like, this intrusive artwork.

◇Barbara Pollack

Art Critic and Curator, International Art Critics Association, USA.